The South Asian island was plunged into crisis after a cascade of rating downgrades following large tax cuts in 2019 and the loss of tourism during the pandemic, leaving it unable to tap global markets.

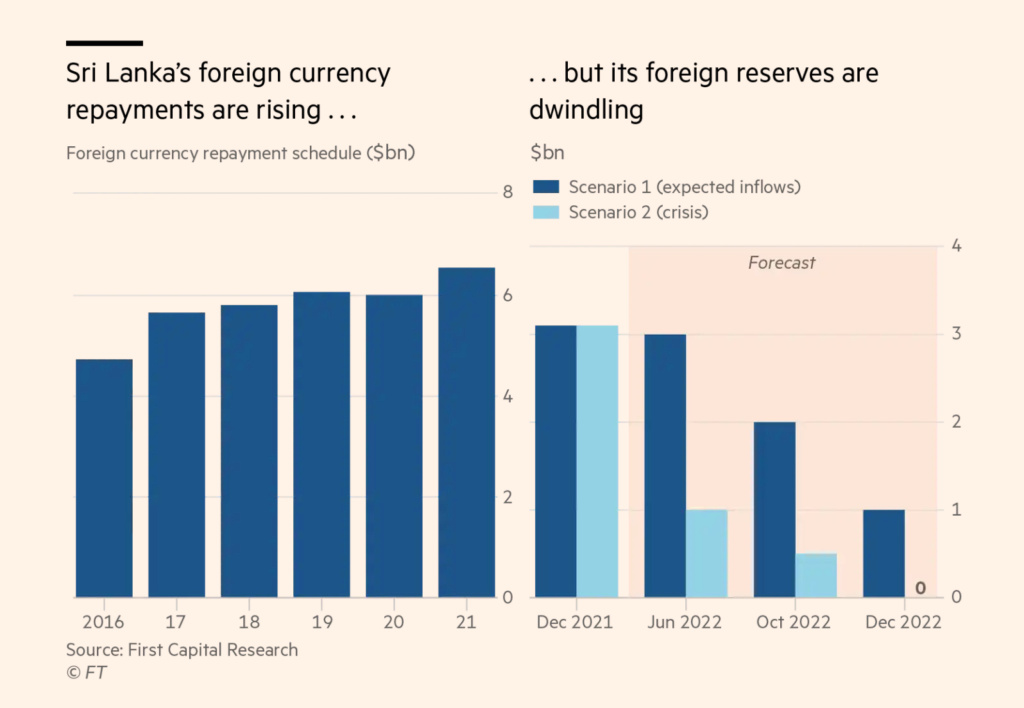

Sri Lanka owes $15bn in bonds, mostly dollar-denominated, of a total $45bn long-term debt, according to the World Bank. It needs to pay about $7bn this year in interest and debt repayments but its foreign reserves have dwindled to less than $3bn.

The government’s next big challenge is a $1bn bond repayment due in July. If it fails to pay, it would join countries including Suriname, Belize, Zambia, and Ecuador in defaulting on its debt following the pandemic.

“They are demonstrating an amazing willingness to pay,” said Richard House, head of emerging market debt at Allianz Global Investors. “But why they would want to, I’m a bit flabbergasted. They are bankrupt, pretty much.”

He added: “They are wasting precious FX reserves. It’s just delaying the inevitable.”

Sri Lanka’s finance minister, Basil Rajapaksa, told the Financial Times last month that the country was “trying all options” to avoid default. But its dollar-denominated bonds are trading at near half their face value, a level that implies a high probability investors will not be repaid in full.

“At these levels, a restructuring over the next 12 months should be the base-case scenario,” said Polina Kurdyavko, head of emerging market debt at BlueBay Asset Management, which holds some Sri Lankan bonds. “I find it difficult to see them muddling through this year.”

Sri Lanka first tapped bond markets more than a decade ago, taking advantage of western investors’ thirst for high-yielding assets as it sought to finance reconstruction following a civil war that ended in 2009.

It has since become an important player in global sovereign debt markets and has borrowed billions from countries including China and Japan. Sri Lanka has never defaulted and its successive governments have been known for a market-friendly approach.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government has said the country will survive the economic crisis by attracting more tourists and boosting exports, but many investors view this as unrealistic. It has also negotiated more than $1bn in relief from India and has asked China to restructure its debt.

The shortage of dollars has begun to inflict deep economic pain on the import-dependent nation. Cities including the commercial capital Colombo face regular electricity blackouts because of fuel shortages, while other essentials such as cement or milk powder are in short supply, resulting in double-digit domestic inflation.

“People don’t need to suffer like this,” said Roshan Rashid, the owner of a ceramics shop in Colombo. Prices of the tiles he buys have more than doubled after the government banned imports in an effort to save dollars.

Ahilan Kadirgamar, a sociologist at the University of Jaffna who works with rural co-operatives, said the economic crisis was “by far the worst kind we’ve been through since independence” in 1948.

He argued that the government needed to drastically reduce imports and prioritise distribution of food, medicine and other essentials. “Poverty is more visible now. People are finding it harder to cook one or two meals a day,” he said.

There are signs authorities are rethinking their approach. Rajapaksa told the FT that the government was “negotiating with everybody” including bondholders and was weighing an approach to the IMF.

Sri Lanka has previously entered 16 programmes with the IMF, but about half of those were not completed. Investors said the fund was likely to insist on a restructuring before providing assistance.

“If the IMF were to extend a programme, it would necessarily involve some level of restructuring,” said Daniel Alphonsus, a former adviser to Sri Lanka’s finance ministry under the previous government.

Manjuka Fernandopulle, an independent lawyer in Colombo who specialises in debt restructuring, said the “IMF is the only credible option”.

But the presence of a wide range of creditors — particularly the heavy borrowing from China — could complicate attempts to restructure the debt.

In Zambia, where authorities are restructuring debts of about $15bn to secure an IMF loan, the process has been beset by accusations from bondholders that the government was favouring Chinese creditors.

Kurdyavko said: “It’s important to have all creditors on board. We want to avoid the dynamic where one group tries to push a certain angle to disadvantage the others.”

Despite the threat of default, some investors are contemplating whether now is the time to buy Sri Lanka bonds, as prices are so low. House said bondholders could end up receiving more than 50 cents on the dollar in a restructuring deal.

“It’s been a terrible credit for a long time, it’s now being priced as a terrible credit,” he said.

https://www.ft.com/content/09e1159f-9c45-4379-b862-98cb5e30a4da

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

would enable you to enjoy an array of other services such as Member Rankings, User Groups, Own Posts & Profile, Exclusive Research, Live Chat Box etc..

Home

Home